As we move towards electrification of our homes and businesses one of the things we need to worry about is the cost of this transition. Documents such as the City of Chico’s 2021 Climate Action Plan and statements made by pro-electrification groups claim that transitioning from natural gas appliances to electric ones is cost effective. Is it?

Converting Electricity and Natural Gas to Heat Energy

We use natural gas and propane in our homes to provide thermal (heat) energy to heat air, water, and our food as well as dry our clothes. In the hierarchy of energy forms thermal energy is considered the lowest form of energy. When energy is converted from one form to another, to get work done, thermal energy is always produced, typically as a waste product. For example, when we eat food (chemical energy) our bodies convert it to mechanical energy (to move our limbs) and electrical energy (to power our thinking, senses, and metabolism) in a series of steps known as the “Krebs cycle”. The Krebs cycle takes sugar molecules and converts them with the help of oxygen into energy, heat, and carbon dioxide. We end up generating a tremendous amount of heat as a waste product that we need to get rid of by evaporating water from our skin and radiating heat so we can function at a relatively constant temperature (97 to 99 degrees).

Converting natural gas and propane into heat energy is a very simple process. Natural gas, or methane (a one-carbon molecule, CH4) and propane (a three-carbon molecule, C3H8) is combined with oxygen in the presence of a flame (oxidized or burned) to produce carbon dioxide (CO2) and water (H2O). This process gives off a tremendous amount of heat energy. It is the heat energy we want in this process and the carbon dioxide and water are the waste products. This conversion process is much more efficient than the standard (fossil fuel) electrical production process.

Producing electricity, on the other hand, is a multi-step process requiring many conversions of different forms of energy, which gives off heat energy as a waste product with each step. The exception here is solar energy, which is one of the most direct methods of producing electricity. Other renewable electrical sources are multi-step processes; however, there are fewer steps and losses with these production methods than the typical thermal electrical method.

The primary way we produce electricity is known as thermal electricity production. A combustible material such as coal, natural gas, and/or wood is mined, pumped, or cut down and burned to heat water to make steam. A lot of energy and multiple transitions went into making fossil fuels, of which only a small portion ends up producing electricity. Steam energy is spins a generator that produces electricity. The waste heat has to be ejected into the atmosphere to cool the steam so that it can be heated again to make steam. According to the Department of Energy’s (DOE) Energy Information Agency (EIA) about 60% of the energy content of fossil fuels is wasted in generation process.

This wasted heat can be used to provide thermal energy for industrial processes, heating communities, and homes. Known as co-generation or CHP (combined heat and power), the waste heat is actually a valuable byproduct of fossil fuel electrical production. Fortunately, or unfortunately, we don’t locate homes next to power plants, or do we?

Electricity produced by a generator at a power plant must be transported to our homes. To do that without wasting a lot of electricity as heat because of the resistance in the power lines, the electricity has to be transformed to a very-high voltage, that is unusable at those voltages. Electricity flows through the power lines to substations where the super-high transmission voltage is reduced (stepped down) to a lower, but still a high, unusable voltage for distribution throughout a city or an area. High voltage electricity then enters transformers on power poles or underground, next to our homes and transform the high voltage electricity to a lower voltage (120/240 volts) that we can use in our homes. At each step of the process energy is lost. According to the Department of Energy’s (DOE) Energy Information Agency (EIA) roughly 5% of the energy is lost during the transmission and distribution of electricity from the power plant to the end uses.

Hydroelectric electricity is a little more direct, there is no combustion process. Gravity in the form of falling water turns a generator that produces electricity that is transformed, transmitted, and distributed. Much less wasted energy in this process even though generators are not 100% efficient in converting mechanical energy to electrical energy.

Solar electric is even more direct. Sunlight falling on a solar panel produces electrons (direct current DC) which are then transformed to alternating current (AC) for use in your home. Even though solar panels convert only 15 – 22 percent of the sunlight falling on the panel it is a more direct way to produce electricity.

Now let’s look at natural gas (or propane). Gas is piped into a home where it is burned in a furnace, stove, oven, or water heater. Heat from the combustion process heats the air, water, or food directly. There is no transformation of different energy forms but, energy is used to extract natural gas and transport it in pipelines to our power stations and homes.

Electrical energy is considered to be a high-value energy source. It is very useful for lighting, electronics, motors, and other high-value uses. Heat energy is a low-value energy and while extremely necessary, on the scale of energy values it is pretty low.

If we look at the Laws of Thermodynamics we see that the First Law states that energy cannot be created nor destroyed, it can only be transformed from one form to another. We follow the first law when we transform from natural gas (chemical energy) to steam (thermal energy) to electrical energy. At the same time the Second Law of Thermodynamics states that whenever we convert or transform one form of energy to another some is lost from the system to the environment. In other words, the law of diminishing returns. Every conversion from one form of energy to another is always less than 100%.

The more steps or conversions an energy form to make it useful the more the available energy is lost to the system. Using coal to make electricity is a huge waste in energy. It took a massive amount of energy to make coal, petroleum, and natural gas and millions of years to do it. Then 60% or more of it’s available energy is used to mine, process, transport, convert (generation) to electricity, transmit and distribute it. Then we use this electrical energy to heat air, water, and food which wastes even more of the available energy as it is converted back to heat energy. Each step in the process incurs a cost, the more steps the more it costs to use it.

As we’ve seen all the steps it takes to convert an unusable energy source to a usable one adds to the cost. Solar electric and wind electric are the most direct ways to produce and utilize electricity, and theoretically the cheapest way to produce electricity.

Cost of Electricity vs Natural Gas

The cost of energy depends on a number of factors, many of which were discussed above. The amount you pay for it, once the electricity is in an electric utility’s system is a whole other process. Utility tariffs (rate schedules) are complicated and trying to understand them is very involved. I will address energy bills in another blog. This blog post will focus on the cost of converting energy from one form to another in our homes.

Electrical Costs

Electrical energy (power) is measured in watts. Watts are a very small unit of energy and not useful for billing purposes, so we gather watts into billable amounts, kilowatts. A kilowatt is 1,000 watts. When we use electricity, we use it for a period of time, so there is a time component to electrical power. Hours are more convenient for billing purposes than minutes, so we get billed in kilowatt hours (kWhs).

What do we pay for a kWh?

In Pacific Gas and Electric’s territory we are currently (Oct. 6, 2022) paying almost $.50 a kWh (peak rate is $0.49 and off-peak is $0.43). These rates will drop significantly during the winter (winter peak rate is $0.39 and off-peak is $0.37). These rates have more than doubled over the past five years and PG&E is now one of the highest cost utility companies in the US.

PG&E Electric Rates (October 2022)

| Electricity | Summer Rates | Winter Rates | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak | Off-Peak | Peak | Off-Peak | |

| kWh Cost | $0.49 | $0.43 | $0.39 | $0.37 |

| Baseline Cost/kWh | $0.40 | $0.34 | $0.30 | $0.28 |

When PG&E changed to a Time-of-Use Rate Schedule they kept the Tiered Rate Schedule as part of the TOU rates. Once you exceed your baseline electrical consumption you will be charged at the “normal” rate for peak and off-peak. These rates are not static and seem to change rather frequently.

Natural Gas Costs

Natural gas is metered at our homes in cubic feet (cu.ft.) but we are billed by the “therm”. One therm is 100,000 BTUs (British Thermal Units) of heat energy. One cubic foot of natural gas is approximately 1,037 BTUs of heat energy. The heat energy content of natural gas varies requiring PG&E to use a multiplier that is based on the energy content of natural gas as tested by the utility company. If you look at a portion of my most recent gas bill you will see the cubic feet to therm multiplication factor is 1.028263. A cubic foot of natural gas in this case is equal to 1,028 BTUs.

What does a therm of Natural Gas cost?

Like electricity the price of natural gas is a combination of a number of factors. The greatest of which is the cost to purchase it, which varies throughout the year. The price also varies by season. In the past summer gas prices are much higher and winter prices lower; however, because of shortages in availability in the winter, winter prices are much higher than summer prices.

One therm of natural gas is priced at $2.12 for tier one rates on October 6, 2022, and is supposed to be close to $3.00 a therm by January.

The Cost per BTU for Electricity and Natural Gas

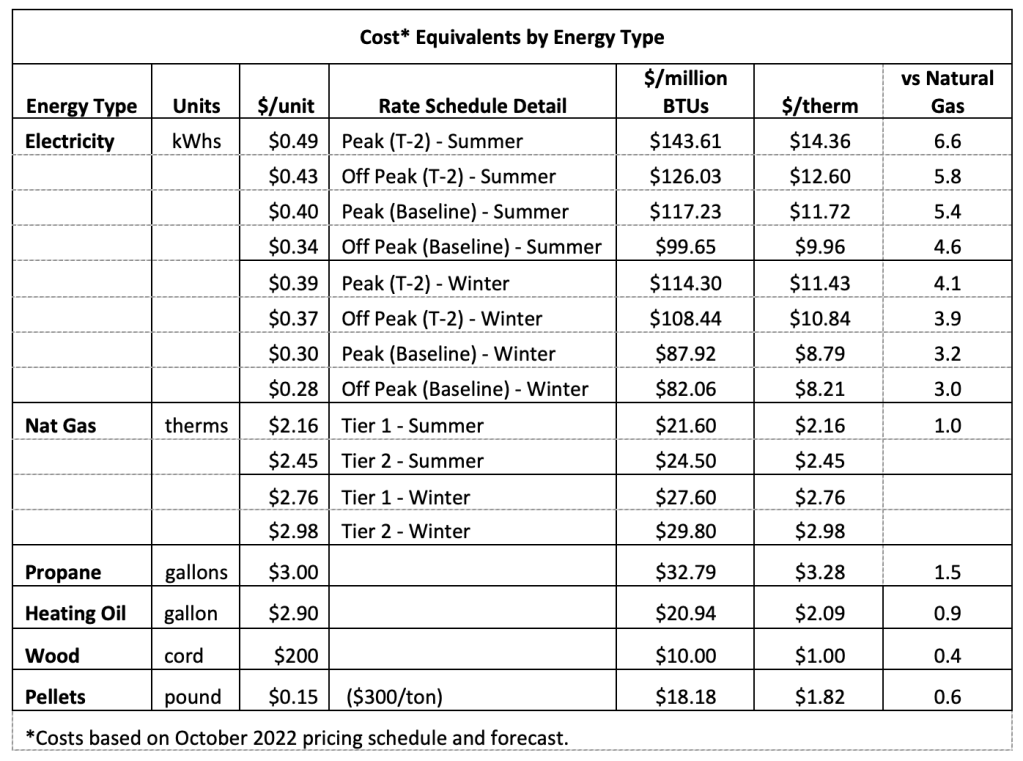

We need a common value to compare to determine the “cost effectiveness” of changing out natural gas appliances with electric ones. Since heat energy in the US is measured in British Thermal Units or BTUs so we need convert the costs per unit of electricity (kWhs) with the equivalent amount of natural gas (therms) per BTU. To do this we will determine the cost per million BTUs (one million BTUs is 10 therms or 293 kWhs).

Heat Energy Equivalents of Common Heating Fuels

- Electricity = 3,412 BTUs/kWh

- Natural Gas = 100,000 BTUs/therm

- Propane = 91,500 BTUs/gallon

- Heating Oil = 138,500 BTUs/gallon

- Wood = 200,000 BTUs/cord (average, actual depends on species and water content)

- Pellets = 8,250 BTUs/pound (dry)

If we compare the different residential energy sources used for space heating (water heating and cooking fuels are limited to natural gas, propane, and electricity) the lowest cost for heating energy (per therm or BTU) is firewood, followed by heating oil, and propane while electricity is the highest. Because of the way PG&E’s rates are scheduled a customer may have four different prices (Baseline Peak, Baseline Off-Peak, Peak, and Off-Peak rates) for electricity in a single billing period. During the summer electricity may be 5 to 7 times more costly per BTU than natural gas, while in the winter because of higher natural gas prices and lower electrical costs, electricity is only 3 to 4 times more costly on a BTU basis.

Using electricity for heating (electrical resistance heaters) ranges from 3 to 7 times more costly than natural gas on a BTU (or therm) basis. However, using an electric heat pump, because of its high COP (coefficient of performance) or efficiency the cost to provide heat is almost the same as for a 80% efficient natural gas furnace.

In the winter, for PG&E service, the cost difference for heat energy equivalents between electricity and natural gas decreases because the price of natural gas increases (from $2.16 to $2.76) while the price of electricity decreases (from $0.49 to $0.39 peak).